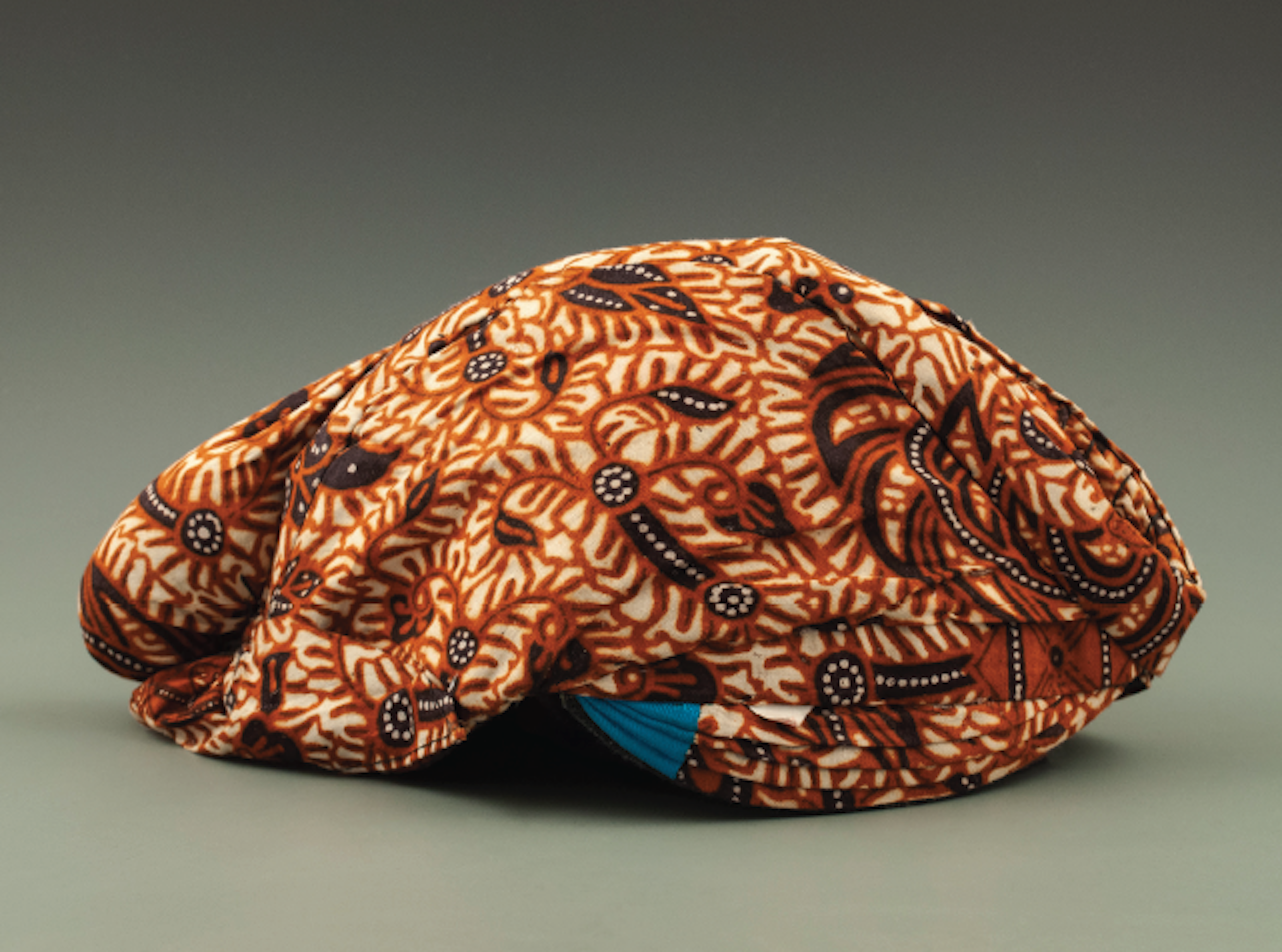

Traditional Blangkon Royal Court Hat

Java, 1984

Near midnight in Yogyakarta, as the sidewalk vendors packed their wares, I came upon a group of bicycle rickshaw drivers. They squatted on straw mats, laughing and shouting at a flickering light on a veranda. The source of the light, I discovered, was a black-and-white television—playing an American cop show. Despite the incomprehensible story and alien tongue, the men cheered like rugby fans at every change of scene.

A few hours earlier, the sight would have baffled me. That very evening, though, I’d attended my first wayang kulit performance.

Wayang kulit are flat, carved-leather puppets that “perform” behind a backlit screen. Their shadows loom and dissolve, the audience spellbound by myths drawn from 3,000 years of Hindu lore. The art itself is almost as old—even in modern Yogya, few men are more revered than a skillful dalang, or puppet master. As he manipulates the heroes, villains, and clowns—providing narration, dialogue, action, even special effects—the dalang assumes a god-like role.

The performance I attended was still underway when I left. It would continue until dawn, to a live soundtrack provided by the hypnotic, ceaseless rhythms of a gamelan orchestra.

One thing surprised me. Though I’d expected the audience to be enraptured by the ghostly shadows, the screen was arranged so that the blangkon-capped dalang—sitting cross-legged amidst his racks of meticulously crafted puppets—was in plain view. The spectators were as fascinated by the dalang as by the shadow show itself.

It was later that evening that I came upon the assembly of becak drivers, riveted to their TV show. Pausing for a moment, I beheld the bizarre hijinks of the police drama through their eyes. How outrageous those foreign wayang “puppets” must have appeared—and how mysterious the dalang!